Buyers Beware of the Toll-Laden Bridges to Private Markets

Institutional Investors Draw Retail Investors in so They Can Get Out

“In the history of every great catastrophe, you will find some masterly bit of stupidity set fire to the oil-soaked rags.”

—EDWIN LEFEVRE, author of Reminiscences of a Stock Operator

This morning, the acclaimed journalist, Jason Zweig, published an article in the Wall Street Journal revealing disturbing behavior on the part of Hamilton Lane management. Astute analysis by Tim McGlinn, owner of The AltView, was critical to the story. I encourage everybody to read the article and follow Tim on LinkedIn.

The first revelation in Zweig’s article was Hamilton Lane’s use of a valuation methodology that enabled the Hamilton Lane Private Assets Fund to record generous mark ups on secondary investments—often within days of purchasing them.1 This practice is roughly equivalent to paying $1 million for a house, immediately marking it up to $1.25 million based on the last Zillow estimate, and then bragging to your friends that you just made a 25% profit overnight. These markups help explain the lofty and surprisingly stable returns of the Hamilton Lane Private Assets Fund since its inception in September 2020. The technique is especially concerning because there is compelling evidence that private equity fund NAVs have been overstated by GPs over the past several years.2

Needless to say, the Hamilton Lane Private Assets Fund’s hard-to-believe track record has attracted several billion dollars of fresh capital from investors over the past several years. But apparently management was unsatisfied with a 1.40% annual management fee on the fund’s $3.9 billion of AuM.3 In March 2025, Hamilton Lane sweetened their deal by somehow persuading shareholders to waive the 8% preferred return hurdle and then fork over a massive $58 million payment by permitting the distribution of incentive fees on unrealized gains.45 A substantial portion of the unrealized gains was based on the previously described mark ups. It is hard to imagine why a shareholder would vote for this change. Whatever the reason, the decision to treat investors in this manner constitutes the “masterly bit of stupidity,” (not to mention greed), that attracted Tim McGlinn’s and Jason Zweig’s attention.

Private Markets and Late-Stage Speculative Episodes

Zweig’s article was unnerving but hardly surprising. This kind of behavior is typical in the late stage of a speculative cycle, and the U.S. has experienced many over the past 235 years. The first one occurred in 1791 when frenzied traders speculated in “scrip” granting them options to purchase shares in the initial public offering of stock in the First Bank of the United States. Fortunately, Alexander Hamilton’s brilliant financial instincts prevented a catastrophe. Americans have since experienced many more manias and crashes. Each one seemed unique in the moment, but when evaluated over the span of several centuries, a familiar pattern emerges. In 2025, there are clear signs that the pattern has repeated in private markets, and it has now entered the dangerous late stage.

So, how did this happen? Private markets, which include investments such as venture capital, buyouts, real estate, hedge funds, and private credit, were all the rage among institutional investment plans over the past two decades.6 Mesmerized by the exceptional returns of the Yale University Endowment at the turn of the twenty-first century, trustees began shoveling substantial amounts of capital into these markets. Multiple red flags steadily emerged, but they were largely hidden by the slow passage of time. Now, it appears the check for collective complacency is coming due. It is a tragic irony that a company unworthy of bearing Alexander Hamilton’s name may be the proverbial canary in the coal mine alerting investors to the danger.

The remainder of this newsletter reveals seven red flags which strongly suggest that private markets are in the late stage of a classic speculative cycle. At best, this means they are severely overvalued; at worst, it means that at least some segments may qualify as a bubble.

Private Markets Red Flags

🚩 Widespread Acceptance of a Flawed Narrative

🚩 Presence of a Complacent and Siloed Supply Chain

🚩 Large and Increasingly Indiscriminate Capital Inflows

🚩 Unbalanced Media Coverage

🚩 Stealthy Exit of Smart Money

🚩 Aggressive Sales to Retail Investors

🚩 Sudden Loss of Confidence in the Narrative

This newsletter is mainly written for the benefit of retail investors. I fear it will be of limited use to institutional investment plans, as most have already thoroughly polluted their portfolios with private investments. Retail investors, however, are just now being lured into the quagmire. They would be wise to resist temptation. Even if private markets are not outright bubbles, the sheer volume of excess capital all but assures that the vast majority of investors will be unrewarded for the exorbitant fees and hidden risks.

🚩 Red Flag #1: Widespread Acceptance of a Flawed Narrative

“There is no national price bubble [in real estate]. Never has been; never will be.”

—DAVID LEREAH, chief economist of the National Association of Realtors

Beneath the foundations of history’s worst bubbles were widely accepted narratives that ultimately proved to be dead wrong. In the 1810s, American farmers believed that wheat and cotton prices would remain at astronomical levels for many years. In the late 1920s, Wall Street speculators believed that using short-term debt to purchase stocks was safe because the markets would never experience a sustained decline. In the late 1990s, Americans believed that any company with a “.com” placed after its name offered a sure path to riches. In the early 2000s, Americans believed that real estate prices would never decline on a national level.

In the 2020s, it seems almost every institutional and individual investor believes that private markets offer a foolproof way to enhance returns and/or reduce portfolio risk. Few question the validity of this narrative despite mounting evidence that not only is it unlikely to be true in the future, but there is also strong evidence that it failed to materialize in the past.7 Even more frighteningly, to this day, it is nearly impossible to find anybody who contemplates the possibility that private markets are susceptible to bubbles.

A paradox of investing is that speculative excesses happen only when the vast majority of investors believe they can’t happen. It is reminiscent of a famous scene in the movie The Usual Suspects, when a shadowy villain Keyser Söze explained how the myth of his existence enabled him to achieve maximum surprise. After completing his crime spree, Söze ended the movie by declaring, “the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” Speculative episodes thrive under similar conditions.

🚩 Red Flag #2: Presence of a Complacent and Siloed Supply Chain

“What are the odds that people will make smart decisions about money if they don’t need to make smart decisions—if they can get rich making dumb decisions?”8

—MICHAEL LEWIS, author of The Big Short

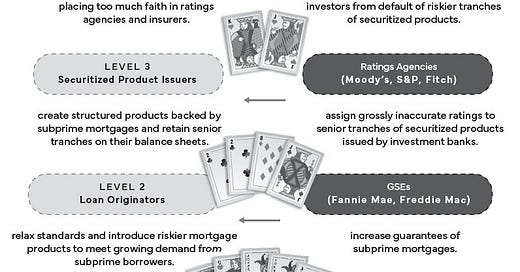

A few years before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2009, a handful of investors, such as Mike Burry and Steve Eisman, placed large bets on the potential collapse of securities tied to the real estate market. In the book, The Big Short, they were portrayed as geniuses—and, to be clear, they deserve a lot of credit for their investment acumen—but the most important factor driving their success was not sufficiently explained. The real estate bubble in the early 2000s was extremely difficult to detect because it was visible only to a small handful of people who understood each segment of the real estate and mortgage-backed security supply chain. Even the most vocal real estate skeptics usually failed to appreciate the full scale of the problem because they only understood a few segments.

People like Mike Burry and Steve Eisman were exceptions. They saw how individuals with no real estate experience were using massive amounts of debt to indiscriminately buy properties with the sole intention of flipping them for a quick profit. They saw how mortgage lenders were motivated only by sales volume, which led them to issue loans with little regard for the borrower’s ability to pay. They saw how investment banks purchased and repackaged these loans into risky products that were nevertheless rated triple-A. Finally, they saw how lax ratings agencies, specialized insurers, GSEs, and the financial media reinforced the faulty narrative, giving speculators a false sense of security. The figure below from Investing in U.S. Financial History shows how this supply chain worked.

Source: Investing in U.S. Financial History: Understanding the Past to Forecast the Future (February 2024).

On the surface, the supply chain in private markets looks quite different, but it is similar in the sense that each segment adds incremental risk, and few investors appreciate how these risks compound as products move along the assembly line. Moreover, participants in the supply chain are so hyper-focused on extracting value from their particular segment that they have little care for the risks embedded in the products that pop out at the end.

Several private markets skeptics with whom I have spoken place inordinate blame on the proverbial wolves of Wall Street, which largely consist of private fund managers. I respectfully disagree, but only because, while I acknowledge that the wolves of Wall Street tend to behave like insatiable gluttons, this makes them highly predictable. Like a pet dog, if you keep feeding them, they will keep eating until they vomit all over the house. The trick is to stop feeding them before they overeat.

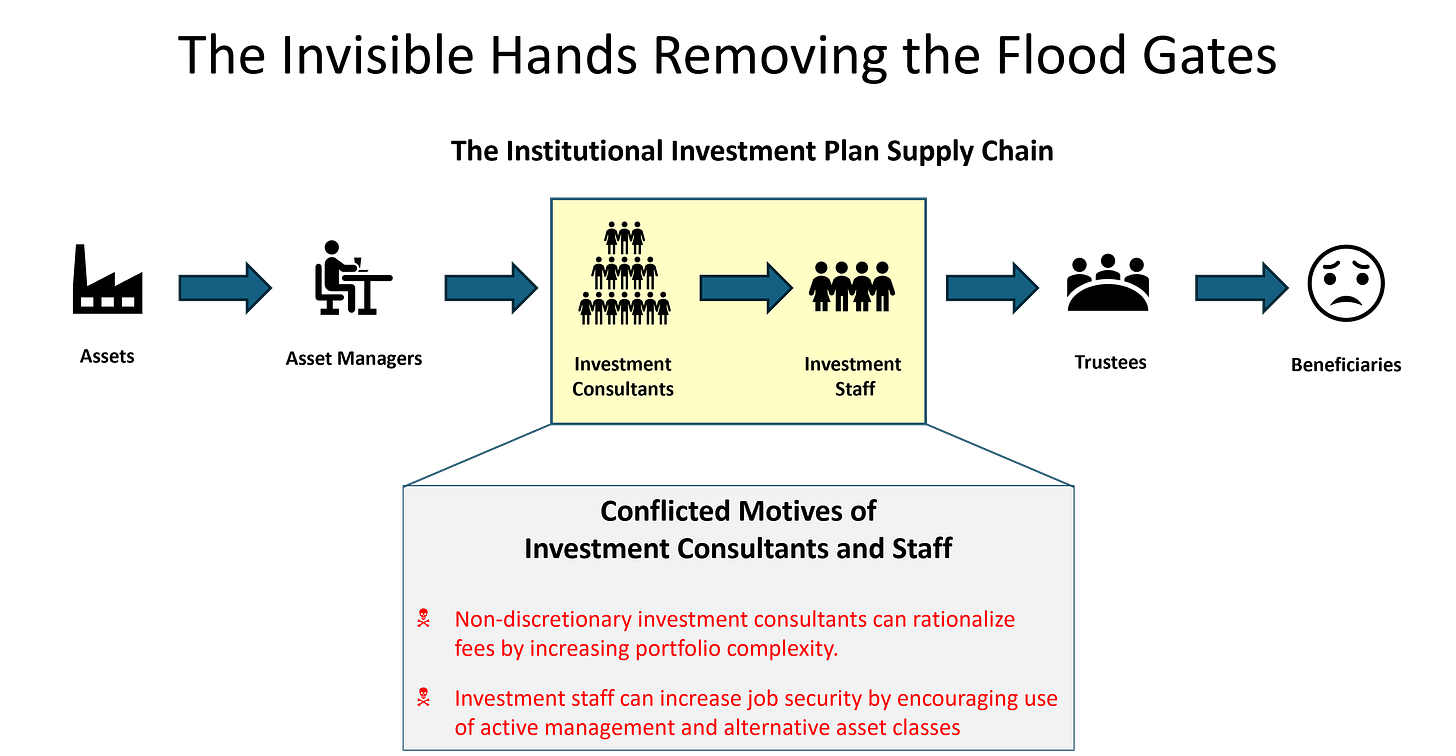

This is why I believe the more insidious link in the private markets supply chain consists of investment consulting firms and investment plan staff members. For more than twenty years, they have encouraged trustees to continuously increase allocations well beyond a point that made sense. Their recommendations were often driven by dubious return assumptions, embarrassingly light due diligence, and the presence of an unstated conflict of interest that biases their recommendations toward serving their business interests and career aspirations. Moreover, neither consulting firms nor plan staff receive much attention from regulatory authorities.9 These were important points in a recent presentation I delivered at the CFA Institute’s CFA Institute Live 2025 conference in Chicago. It can be downloaded for free in this LinkedIn post, and the dynamic was discussed further in my interview with Lotta Moberg, PhD, CFA on the CFA Institute’s Enterprising Investor podcast on May 5, 2025. The graphic below shows the institutional investment plan supply chain, highlighting the particularly damaging role of investment consultants and investment plan staff.

🚩 Red Flag #3: Large and Increasingly Indiscriminate Capital Inflows

“‘An Aristocracy of Successful Investors’ advertised a new guide to investment. The headline read: “He made $70,000 after reading, “Beating the Stock Market.” No doubt whoever it was did. He might have made it without reading the volume or without being able to read.”

—JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH, author of The Great Crash 1929

Fundamentally, an asset bubble is nothing more than a colossal imbalance of supply and demand. The resulting scarcity of attractive investment opportunities causes prices of sound investments to rise to unattractive levels and compels fund managers to allocate the excess to unworthy investments and/or outright frauds. Eventually, a critical mass of investors awakes to this reality, capital flows reverse, and the speculative cycle ends with a crash.

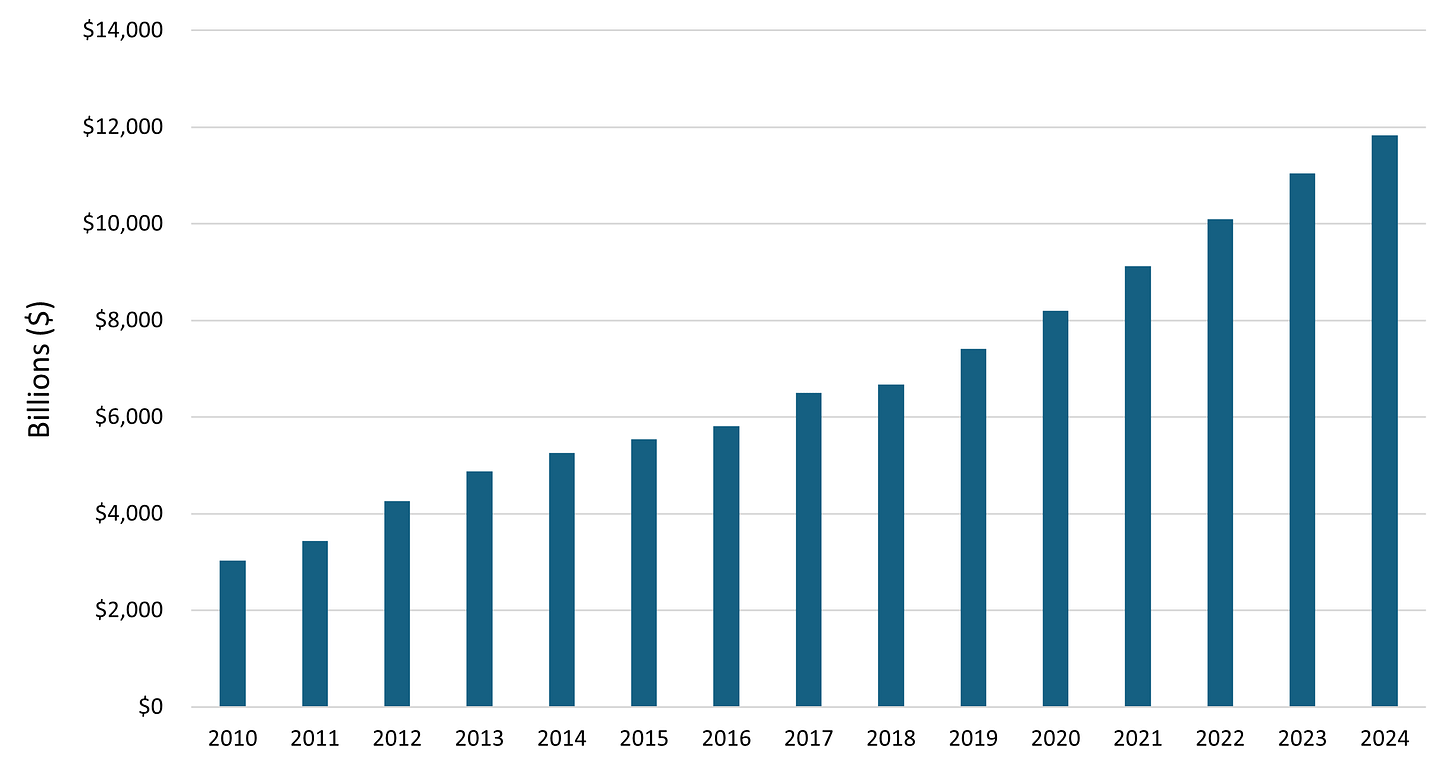

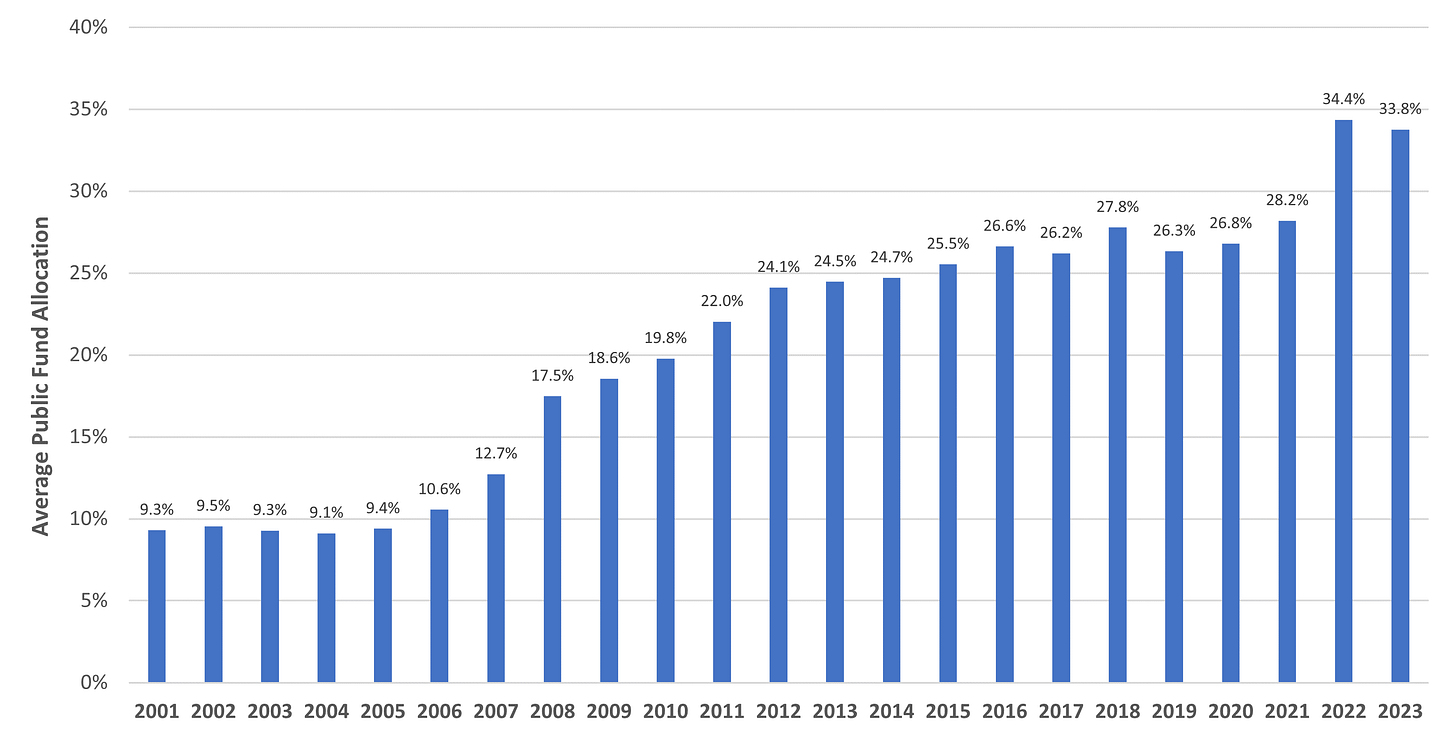

The flood of capital into private markets has now persisted for more than two decades. It began soon after the late CIO of the Yale Investments Office, David Swensen, published Pioneering Portfolio Management in 2000. Followers assumed they could improve their performance by bluntly allocating to alternative asset classes. Few paused to consider the fact that Swensen was both uniquely talented and early to enter these markets. Replicating his performance was never likely for the masses. Nevertheless, by 2010, AuM in key private markets was increasing at more than 10% per year. Figure 1 shows total AuM of three major private markets (private equity, hedge funds, and private credit). Figure 2 shows the rapid growth of public pension plan allocations, which was a significant driver of AuM growth.

Figure 1: Private Equity, Hedge Fund, and Private Credit AuM ($Billions)

(2010-2024)

Source: Prequin.

Figure 2: Average Public Pension Plan Allocation to Alternative Investments (%) (2001-2023)

Sources: Equable (2024).

🚩 Red Flag #4: Unbalanced Media Coverage

“You have to throw out all of the matrices and formulas and texts that existed before the Web. You have to throw them away because they can’t make money for you anymore, and that is all that matters. We don’t use price-to-earnings multiples anymore…If we talk about price-to-book, we have already gone astray. If we use any of what Graham and Dodd teach us, we wouldn’t have a dime under management.”

—JIM CRAMER, host of Mad Money (February 29, 2000)10

The worst speculative episodes in U.S. history were amplified by the media. In 1928 and 1929, it was rare to see journalists challenge the legitimacy of the Great Bull Market. In fact, when the businessman and economist, Roger Babson, presciently predicted the Great Crash of 1929 less than two months before it arrived, he was almost universally dismissed by journalists. A similar phenomenon occurred in the late 1990s. It was rare to find journalists willing to challenge the use of senseless metrics, such as user growth, to rationalize ridiculous dot-com stock valuations. It also happened during the real estate bubble in the early 2000s, as few journalists challenged the easily disprovable narrative that U.S. real estate prices have never declined on a national level.11

In 2025, it is rare to find anybody in the financial media who questions the merits of investing in private markets or is even willing to entertain the possibility of a bubble. This is precisely the type of groupthink that adds momentum to speculative cycles.

Source: “Financial Markets.” The New York Times. (September 9, 1929), 34.

Red Flag #5: Stealthy Flight of Smart Money

“Once a majority of players adopts a heretofore contrarian position, the minority view becomes the widely held perspective. Only an unusual few consistently take positions truly at odds with conventional wisdom.”

—DAVID SWENSEN, late CIO of the Yale Investments Office

In 1928 and 1929, a handful of astute investors, such as Bernard Baruch, Joseph Kennedy, and Charles Merrill, sensed the market had become completely detached from reality, and they sold the majority of their holdings in U.S. stocks. But if they dared to share their opinions, they were subjected to ruthless ridicule. In fact, Charles Merrill was so disturbed by the criticism that he feared he had lost his mind. In 1928, it took multiple visits to a psychiatrist before he regained confidence in his sanity. Of course, when the October 1929 crash arrived, Merrill, Baruch, and Kennedy were vindicated, but it was tough going in the meanwhile.12

On April 17, 2025, Secondaries Investor reported that the Yale Investments Office was exploring the sale of up to $6 billion in private equity investments, which would constitute roughly 30% of Yale’s total holdings in private markets. Secondaries Investor also stated that this transaction would constitute the endowment’s first known secondary sale. Yale confirmed the potential sale, but refused to specify the target amount. But, sure enough, on June 5, 2025, Bloomberg reported that Yale was nearing a deal to close a sale of $2.5 billion of its venture capital portfolio.13

Some people argue that Yale’s potential sale of private equity holdings is merely a response to the Trump Administration’s aggressive funding cuts for Ivy League institutions. This may be true, but my suspicion is that it is only a minor part of the story. Yale pioneered investments in private markets in the 1980s, but capital was in short supply and attractive opportunities were more plentiful at the time. The opposite is true in 2025. The Yale Investments Office is widely regarded as one of the more astute investors, which makes it plausible that their proposed sale of private equity is a dash for the exit.

Red Flag #6: Aggressive Sales to Retail Investors

“The most notable piece of speculative architecture of the late 20s, and the one by which, more than any other device, the public demand for common stocks were satisfied, was the investment trust or company.”

—JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH, author of the Great Crash 1929

For most of the 1800s, the U.S. relied on foreign capital to fund the building of critical infrastructure and commercialization of innovation. Americans certainly benefitted, but foreign investors often suffered from a pernicious and repetitive cycle. It would begin with the introduction of an innovation, such as canals, steamships, and railroads. Foreign investors would enthusiastically flood the market with capital, which eventually resulted in massive overbuilding. The market would eventually crash, and foreigners would then indiscriminately sell their securities for a fraction of their cost. At that point, astute American investors would repurchase shares in the few sound companies that remained, which enabled them to own the infrastructure that was built on somebody else’s dime.

This phenomenon ended in the early 1900s when the U.S. began running large budget surpluses. Foreigners lacked sufficient capital to meet America’s needs, which compelled the wolves of Wall Street to begin targeting their own. From that moment forward, it became common for speculative cycles to end after Wall Street firms exhausted the funds of the last and most vulnerable cohort of capital providers: retail investors. Starting in the 1920s, the most common vehicle used to extract capital from retail investors was the investment company, which is now more commonly referred to as a mutual fund or 40-Act fund.

Over the past twenty five years, private markets were largely reserved for institutional investment plans and ultra high net worth investors. But as is always the case in speculative cycles, overly enthusiastic investors eventually flooded the market with excess capital. The classic cycle of overbuilding and malinvestment ensued. According to a June 2, 2025 article published in the Wall Street Journal, a backlog of approximately 30,000 companies now sits on the balance sheets of private equity firms. The prospect of exiting these investments at acceptable prices is daunting.14

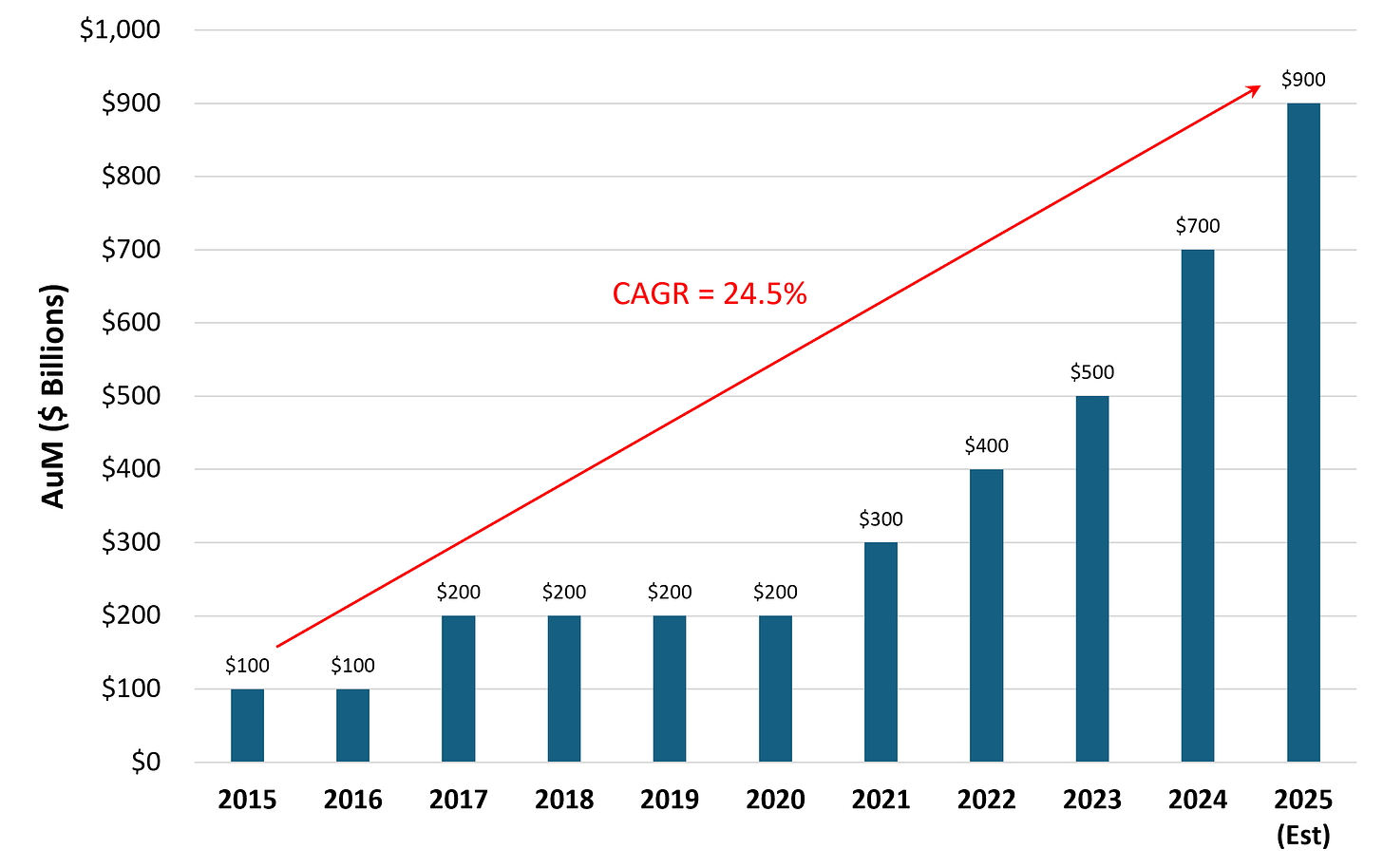

Over-allocated institutional investment plans and private fund managers are now desperately seeking exits, which helps explain their sudden interest in bringing private markets to retail investors. Once again, a vehicle of choice is the 40-Act fund. Heavy marketing to retail investors has led to massive inflows into evergreen funds with fancy names, such as interval funds and continuation funds (see Figure 3).

Rather than explaining the mechanics of each type of evergreen fund, it is easier to describe what most of them likely contain: the funds that private fund managers either can’t sell and/or institutional investors can no longer bear to look at. But, if this is the case, how is it that many newly minted 40-Act funds are advertising lofty returns that are eerily stable? Well, if the performance seems too good to be true, perhaps it is too good to be true. This brings us to the final and most disturbing red flag.

Figure 3: Growth of Evergreen Funds ($ Billions) (2015-2025est)

Sources: Pitchbook, CapGemini World Report Series 2024 (January 2025), Hamilton Lane.

Red Flag #7: Sudden Loss of Confidence in the Narrative

“Human nature being what it is, small loopholes are likely to be exploited until they become big ones, and big ones until they turn into financial disasters.”

—SETH KLARMAN, owner of Baupost Group

Speculative cycles end when a critical mass of investors suddenly loses faith in the flawed narrative on which it was based. This was a factor in the late 1920s when speculators failed to realize that corporate earnings were being padded by interest earnings on call loans that the companies issued to speculators, who then turned around and used the loans to purchase stock in the very same companies that issued them. When the Great Depression began, demand for call loans dried up, and companies suffered from lower demand for their products and the evaporation of interest income on call loans.

This dynamic is what makes the valuation and compensation practices at Hamilton Lane especially unnerving. Many investors were likely drawn to the fund because of its impressive track record, but Zweig’s article raises serious questions as to whether Hamilton Lane grossly overestimated the value of the underlying investments and the corresponding returns. Even more concerning is the fact that Hamilton Lane is not the only fund manager to make liberal use of this alleged loophole. In a previous Wall Street Journal article, Jonathan Weil revealed that StepStone used the same tactic.15 It would be unsurprising if journalists discover that many more funds are employing similar practices. Moreover, it is quite conceivable that pension funds, foundations, endowments, and family offices are employing it as well. This may call into question the quality of their reported returns and the real value of their portfolios. In other words, it is quite possible that Zweig’s article is the proverbial canary in the coal mine that signals the presence of a much graver hazard.

Concluding Thoughts: This is the Place to Stop the Trouble

“It is easy enough to burst a bubble. To incise it with a needle so that it subsides gradually is an operation of undoubted delicacy.”

—JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH, author of the Great Crash 1929

On October 22, 1907, the Panic of 1907 was in full force. A bank run had taken down the Knickerbocker Trust; depositors were lining up at banks and trusts throughout the city; and it appeared the Trust Company of America would be the next institution to fall. J. Pierpont Morgan hastily assembled his top lieutenants, and they concluded that, if not for the bank runs, the Trust Company of America was solvent. Morgan immediately convened the CEOs of the leading trusts, and by the next morning they had orchestrated a rescue. It was later revealed that after concluding the analysis of the Trust Company’s balance sheet, Morgan stated “This is the place to stop the trouble, then.”

Source: “Aid Trust Co. of America.” The New York Times. (October 23, 1907), 1.

Researching the 235-year financial history of the U.S. taught me to never ignore the red flags that typically signal the approaching end of a speculative cycle. Over the past few years, I have often pondered whether a loud enough voice of reason in 1927, 1997, or 2003 could have prevented the subsequent bubbles and corresponding crashes.

In 2025, it is uncertain whether the flood of capital in private markets qualifies as a bubble, but after considering all the red flags, it would be wise to assume that it does. At a minimum, the excess supply of capital—not to mention the obscenely high fees—will prevent the vast majority of investors from generating attractive returns. This makes the cost of avoiding this purported “opportunity” negligible compared to the danger of participating in it. People need to understand the true purpose of the toll-laden bridges leading to private markets. They are escape routes for overindulgent investors who are desperately seeking a way out. Retail investors would be wise to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors and run from these bridges. If they do, they can record a true rarity in the annals of financial history by forcing complacent investment consultants, investment advisors, investment plan staff, and fund managers to suffer the full consequences of the mess they created.

I hope this newsletter helps counteract what, by all measures, seems like yet another episode of irrational exuberance. But even if it fails to persuade most investors to avoid private markets, perhaps it will spare a few. On this point, I turn to Charles Merrill for inspiration. He couldn’t stop the Great Crash of 1929, but he spared at least one person’s fortune. After his final office visit, Merrill’s psychiatrist proudly revealed multiple brokerage statements proving that he had sold all of his stock. He then explained, “Mr. Merrill, you are so crazy that I want to show you I have not a single share of stock in my accounts.” By following Merrill’s advice, his psychiatrist entered the Great Depression with abundant reserves. Perhaps this newsletter will offer similar protection to somebody today.16

Purchase Investing in U.S. Financial History

Investing in U.S. Financial History is available in hardcover, audiobook, and eBook formats. Please note, however, that the eBook version was published in fixed format layout to ensure that graphics are more easily viewed. The eBook is ONLY intended to be read on large screens, such as tablets, laptops, or desktop computers.

Disclaimer: This is a personal newsletter written by Mark Higgins, CFA, CFP, in his individual capacity. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or practices of IFA or any other organization or entity with which the author is affiliated. This content is intended for informational and educational purposes only; it does not constitute professional investment advice, an offer, solicitation, or endorsement of any specific financial strategy, product, or service. The discussion contains the author’s opinions based on publicly available information and should not be interpreted as factual or predictive of future events.

Nothing in this newsletter should be construed as a guarantee of investment results, nor should past performance discussed herein be taken as indicative of future outcomes. Investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal, and investors should consult their financial adviser or other qualified professional before making investment decisions. Additionally, every effort has been made to ensure an accurate portrayal of market practices and conditions, but the author disclaims responsibility for errors, oversimplifications, or omissions. By publishing this newsletter, the author aims to foster dialogue and education and does not intend to disparage any individual, organization, or investment strategy. Readers are encouraged to consider differing viewpoints and conduct their own research before forming opinions or investment strategies.

The mark ups were confirmed by reviewing multiple N-CSR and N-CSRS forms submitted to the SEC by the Hamilton Lane Private Assets Fund. The documents covered transactions completed between January 1, 2021 and June 30, 2024. Forms can be accessed here. Hamilton Lane appears to be operating under the assumption that the valuation practices conform with a method allowed under FASB ASC 820, which permits, but does not require, investment companies to use “NAV as a practical expedient” when reporting the value of interests in funds, such as hedge funds, private equity funds, real estate funds, venture capital funds, commodity funds, and funds of funds.

A recent report by MSCI, Inc. revealed that from 2022 to 2024, the multiples paid for companies exiting private equity portfolios were substantially below the multiples used to value companies that remain in the portfolio. Usually the opposite is true. This calls into further question the appropriateness of NAV markups ups on secondary transactions.

AuM of the Hamilton Lane Private Assets Fund is reported based on a fund fact sheet dated as of April 30, 2025. The most current fund fact sheet can be viewed here.

Prior to the change, the Hamilton Lane Private Assets Fund incentive fees were only payable upon the realization of gains. In other words, the assets needed to be sold for the price at which they were valued in the portfolio. This is a critical distinction because if markups on these assets are proven to be excessive, the realized gains could be substantially less than the unrealized gains and unpayable for many years.

Private markets are also frequently referred to as alternative asset classes. This newsletter uses the term private markets, as alternative asset classes can also include certain investments in public markets.

Many recent studies provide evidence that exposure to alternative asset classes have added either no value or negative value to the average plan over medium- and long-term investment horizons for public pensions and endowments. Two of the more recent studies include a study by the Boston College Center for Retirement Research, entitled “Public Pension Investment Update: Have Alternatives Helped or Hurt?” and a recent study by Richard Ennis on the poor performance of university endowments.

Lewis, Michael, "The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine.” (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011).

Most investment consulting firms operate as “non-discretionary” advisors. The Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) places far more scrutiny on discretionary asset managers. In addition, investment plan staff are not considered asset managers, and are therefore subject to considerable less regulatory scrutiny.

Jim Cramer, “The Winners of the New World,” Speech at 6th Annual Internet and Electronic Commerce Conference and Exposition, The Street, February 29, 2000.

The statement that real estate prices had never declined on a national level was especially odd because it could be easily disproven. Real estate prices declined on a national level on multiple occasions, such as in the 1840s and 1930s.

Smith, Winthrop H., Catching Lightning in a Bottle, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

Armental, Maria, “Private Equity Confronts Swollen Investment Backlogs With Dealmaking Stuck.” Wall Street Journal. (June 2, 2025).

Smith, Winthrop H., Catching Lightning in a Bottle, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

This piece was generally good, but there were two significant errors in the chart near the top. Fannie and Freddie did not guarantee subprime. They dabbled in some Alt-A guarantees, but did not go further. Also where you said that that originators "create structured products backed by subprime mortgages and retain senior tranches on their balance sheets." Actually, the opposite of that happened... they sell seniors and mezzanine, and keep the juniors and equity. They keep the most risky parts, because typically they can't be sold. They sell the safe parts so that they can have more cash to originate more loans.