Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, we have experienced a series of financial events that seemed both extreme and unprecedented. These included a 101-year pandemic, sudden-stop financial panic, massive monetary and fiscal stimulus, a spasm of inflation, the reawakening of hawks at the Federal Reserve, and a run on a major commercial bank. Investors responded with a roller coaster of emotions because many lacked the historical context to grasp the potential consequences.

Moreso than most bursts of time, the COVID-19 years demonstrate why studying financial history is so essential. Events that seem unprecedented in the moment become much less threatening when investors arm themselves with knowledge from the distant past. The remainder of this newsletter accentuates this point by recounting an event that occurred one hundred and nine years ago to the day. On July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary shocked the world by declaring war on Serbia, thus triggering the onset of the Great War (which is now referred to as World War I). The unexpected cascade of war declarations by major European powers triggered a market panic that was eerily reminiscent of the one that occurred in March 2020. Despite the passage of more than a century, many lessons from this long-forgotten event remain just as relevant today.

A Tragic Wrong Turn in the Balkans

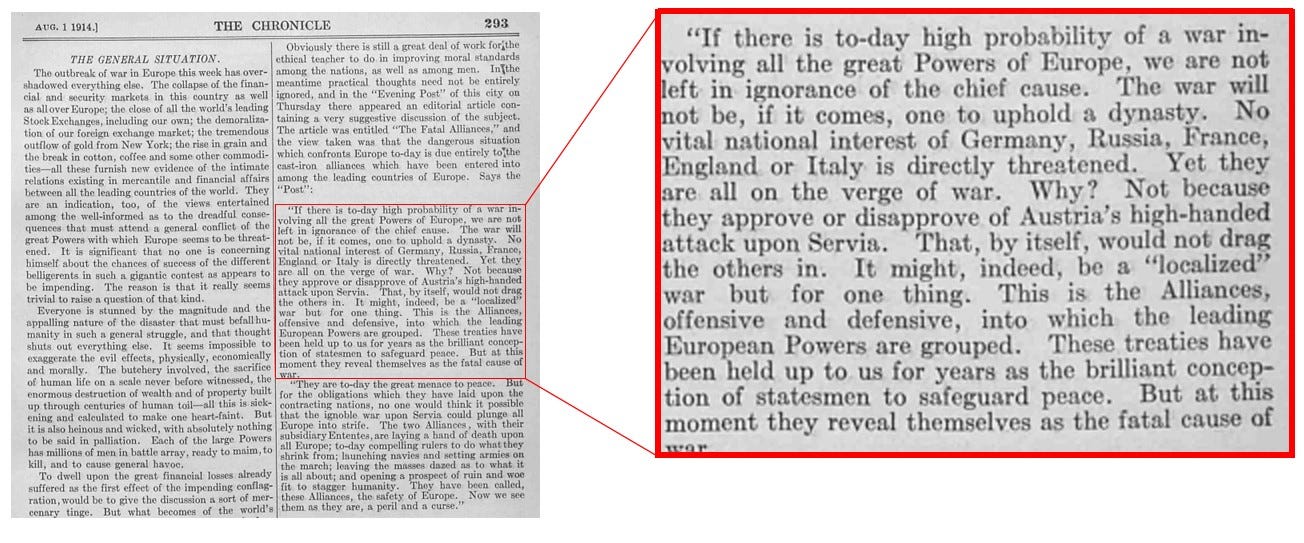

Source: The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, 99, no. 2562, August 1, 1914, 293.

On July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The conflict was triggered by the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie on the streets of Sarajevo only one month earlier. The assassination was literally the result of a wrong turn. The motorcade had suffered an unsuccessful attack less than an hour earlier, but the Archduke insisted on visiting the wounded in the hospital. Unfamiliar with the improvised route, the lead driver made a wrong turn into the heart of Sarajevo. As the motorcade stopped to reverse course, the Archduke’s car stalled within feet of the improvised position of Gavril Princip, a 19-year old member of a Serbian separatist group known as the Black Hand. Princip seized the opportunity and fired his pistol into the vehicle, mortally wounding the Archduke and his wife.1

The assassination was considered tragic by most Europeans, but few imagined it would lead to total war on the entire European continent. The problem, however, was that once Austria-Hungary issued the first war declaration, inflexible defense pacts forced others to join. On one side were the Allied Powers of Great Britain, France, and Russia, and on the other side were the Central Powers of Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a reluctant Italy. As revealed in the above quote, the irony is that the defense pacts that caused the war were specifically designed to prevent it.2

From a financial perspective, the commencement of World War I caught the entire world off guard. Americans were especially surprised because most were too preoccupied with domestic affairs to pay much attention to European geopolitics. Even those concerned with escalating tensions believed that cooler heads would prevail in the end. Most Americans simply could not fathom that Europeans would willingly enter a war with such disastrous consequences.

All Goes Quiet on the Western Front

“It is in the nature of panics to be unforeseen, but the statement may be truly made that some of them can be more unforeseen than others…While the standing armies of Europe were a constant reminder of possible war, and the frequent diplomatic tension between the Great Powers cast repeated war shadows over the financial markets, the American public, at least was entirely unprepared for a world conflagration.”3

George Henry Stebbins Noble

President, New York Stock Exchange

Immediately after Austria-Hungary declared war, the primary concern in the U.S. was the flight of foreign capital, as many Americans feared Europeans would liquidate their investments and ship the proceeds (largely in the form of gold) across the Atlantic to fund war expenses. This fear seemed to be validated during the three-day period beginning on July 27, 1914, as $28.6 million worth of gold left the United States. This was a small fraction of the nation’s nearly $1 billion of gold reserves, but bankers knew that a trickle of outflows could quickly accelerate. This was precisely what happened when bank runs spread during the Panic of 1907. The second concern centered on how the war would affect trade with Europe. If trade collapsed, the U.S. economy could spiral into a deep depression regardless of the flow of gold.4

The timing of World War I was somewhat fortuitous in the sense that memories of the Panic of 1907 were relatively fresh. This preconditioned government and Wall Street leaders to respond aggressively to the first signs of panic — and they did not have to wait long. A full-blown panic erupted on July 30, 1914. Concerned that July 31st would be much worse, prominent bankers, leaders of the New York Stock Exchange, and government leaders convened to discuss a potential closure of the exchange. Despite their initial hesitancy, on the morning of July 31st, it was clear that closure was the only option. All major foreign exchanges had shuttered their doors, leaving U.S. exchanges as the only source of liquidity for the entire world. Just minutes before trading was scheduled to begin, the New York Stock Exchange announced it would close its doors indefinitely. It did not fully reopen until December 15, 1914, making it the longest closure by far in its 231-year history.5

Monetary Response: America Flexes its Currency for the First Time

The closure of the New York Stock Exchange prevented a stock market crash, but the banking system remained fragile. The Federal Reserve Act was signed by President Woodrow Wilson in December 1913, but the system would not be operational until November 1914. Fortunately, the U.S. had a backup. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908 allowed the Treasury to expand the type of securities that national banks could use as collateral to issue banknotes. Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo quickly invoked the Aldrich-Vreeland Act on July 31, 1914, and publicly announced that the Treasury was prepared to authorize the issuance of $500 million in “emergency currency” to counterbalance potential liquidity pressure on the banking system. Over the next several months, banks tapped this liquidity, and currency issued under the Aldrich-Vreeland Act peaked at $364 million in November 1914.6

Fiscal Response: The Spoils of Neutrality

“All past experience, it is true, had proved that foreign war was apt to enrich neutral countries which were large producers of necessaries of life and war supplies…But in no previous war had a neutral state been confronted with what appeared to be the financial insolvency of the entire outside world.”7

Alexander Dana Noyes

Financial Editor, The New York Times

The fear that World War I would negatively impact the U.S. economy proved to be wildly off the mark. Instead, after adopting a policy of neutrality, demand for American exports skyrocketed.8 During the two decades preceding the war, U.S. trade surpluses averaged approximately $450 million per year. By 1916, demand for U.S. exports drove the trade surplus to an average of more than $3 billion per year. Figure 1 below shows the spike in U.S. trade surpluses beginning in 1915.

Figure 1: U.S. Trade Surpluses by Year ($ Millions) (1896-1918)

Source: United States Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1929. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1929).

In summary, when World War I began, Americans feared an economic catastrophe driven by massive withdrawals of gold and a collapse of global trade. Instead, gold flowed in the opposite direction, and American businesses flourished by exporting critical war materiel and commodities. These dynamics set the stage for post-war inflation and created a foundation for speculation in the Roaring 20s, but that is a story for another day.

The Ides of March 2020

“This is no longer a sudden stop of a country. This is a sudden stop of the global economy. It is massive destruction of supply and demand.”9

Mohamed El-Erian

Economist

The COVID-19 financial panic was caused by economic forces that were similar to those that caused the Panic of 1914. In mid-March 2020, the entire world suddenly awoke to the disturbing reality that the COVID-19 virus was uncontainable. Nearly eight billion people simultaneously scrambled to weather a pandemic unlike anything since the outbreak of the Great Influenza in March 1918. In a matter of days, entire segments of the economy shut down, and people confronted the real prospect of a catastrophic, global economic collapse.

The financial reaction to COVID-19 seemed unprecedented, but it would have been instantly recognizable to Americans living in 1914. Much like COVID-19, the outbreak of World War I was sudden, unexpected, and massively disruptive on a global scale. The main difference was that policymakers in 2020 had a more robust set of monetary and fiscal policy tools. In addition, having learned valuable lessons from the Great Depression in the 1930s and GFC in 2008 and 2009, they were willing to use them with little delay. This explains why Americans experienced only a mild and extremely short-lived recession in 2020.

America Flexes its Currency and Stretches its Budget

The U.S. fiscal and monetary responses to COVID-19 were different in many ways from those employed after the onset of World War I, but they were similar enough to produce comparable effects. The policies also looked a lot like the ones employed only 12 years earlier during the GFC. In October 2008, monetary and fiscal policymakers flooded the financial system with liquidity to reverse a self-reinforcing deflationary spiral. Had they failed to act aggressively, a Great Depression-level event was a virtual certainty. This is another way in which the COVID-19 panic was similar to the Panic of 1914. In July 1914, the federal government was pre-conditioned to act quickly and aggressively due to their recent experience with bank runs during the Panic of 1907.10

In 2020, the Federal Reserve and Congress used the same playbook that they used during the GFC — only the response in 2020 was much larger and implemented much more rapidly. Showing the similarity of the two responses, the fiscal programs and Federal Reserve balance sheet expansions during the GFC and COVID-19 are depicted in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 2: Cumulative Fiscal Stimulus and Federal Reserve Balance Sheet Expansion ($ M)

(February 6, 2008 - May 31, 2009)

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; International Monetary Fund; U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Figure 3: Cumulative Fiscal Stimulus and Federal Reserve Balance Sheet Expansion ($ M)

(February 24, 2020 - May 31, 2021)

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; International Monetary Fund; U.S. Department of the Treasury.

The Aftermath

Because the GFC preconditioned Americans to accept massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, the responses were implemented quickly and with dramatic effect. In this respect, the efforts by policymakers were clearly successful. On the other hand, stimulus programs of this magnitude always come with costs. In addition to increasing U.S. debt levels substantially, the responses produced two unwanted side effects: reckless speculation and high levels of inflation. As of July 28, 2023, the Federal Reserve continues to battle with inflation, while speculators continue to use what remains of their excess savings to chase the latest investment fads. Covering these effects fully is beyond the scope of this newsletter, but for those interested in learning more, research papers are available here under the “Covid-19 and Inflation” heading.

Financial History Offers Calm During a Market Storm

"As to new financial instruments, however, experience establishes a firm rule, and on few economic matters is understanding more important and frequently, indeed, more slight. Financial operations do not lend themselves to innovation. What is recurrently so described and celebrated is, without exception, a small variation on an established design, one that owes its distinctive character to the brevity of financial memory. The world of finance hails the invention of the wheel over and over again, often in a slightly more unstable version.”11

John Kenneth Galbraith

Financial Historian and Economist

It is impossible to predict the future with precision, and developing a deeper knowledge of financial history will not enable investors to defy this fundamental law of nature. It does, however, make it easier to maintain situational awareness when markets behave in extreme ways. This, in turn, enables investors to narrow the list of potential scenarios and assign more accurate probabilities to each one. Moreover, knowledge of comparable events from the past enables investors to remain calm and measured when most others become disoriented by the chaos. This is critical because the costliest investment errors are made when investors react emotionally rather than rationally. Finally, knowledge of financial history enables investors to align their perception of the flow of time to that of the market. By virtually extending their investment experience to hundreds of years, they are better equipped to think of investment outcomes in terms of decades rather than days. This makes the daily noise of markets remain where it belongs — in the background.

The events of the past three and a half years provided almost a perfect case study to test the return on investment from the study of financial history. In my opinion, it passed with flying colors. I look forward to sharing more on this topic and others with the publication of Investing in U.S. Financial History in February 2024. The date is fast approaching.

Jesse Greenspan, “The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand,” History, updated February 12, 2020.

James Joll, The Origins of the First World War, (New York: Routledge, 1984), 15.

Henry George Stebbins Noble, The New York Stock Exchange in the Crisis of 1914. (Garden City: The Country Life Press, 1915), 4-5.

“Abrupt Recovery After Further Fall — Our Market Presents Striking Contrast to Those Abroad,” The New York Times, July 30, 1914, 12.

Mark Higgins, Investing in U.S. Financial History [Preprint 2024], (Austin: Greenleaf Book Group, 2024).

Sean Fulmer, “United States: Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency during the Crisis of 1914,” Journal of Financial Crises 4, no. 2 (April 2022): 1156-1179.

Alexander Dana Noyes, The War Period of American Economic Finance 1908-1925. (New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1926), 94.

The United States eventually sided with the Allied Powers, but neutrality was the initial policy.

Mohamed El-Erian. CBSNews. (March 18, 2020).

Economists often draw comparisons between the GFC and the Great Crash of 1929, but the Panic of 1907 offers a better comparison. Both were caused by a massive increases in shadow banking activities. In the early 1900s, the main culprit was state-regulated trust companies, while in the 2000s, it was lending by institutions, such as government-sponsored entities (GSEs), investment banks, and money-market funds.

John Kenneth Galbraith, A Short History of Financial Euphoria, (New York: Penguin, 1990), 19.