The Fed’s Pivot Violated the Rule that Matters Most

The Embers of Inflation Are Not Yet Extinguished

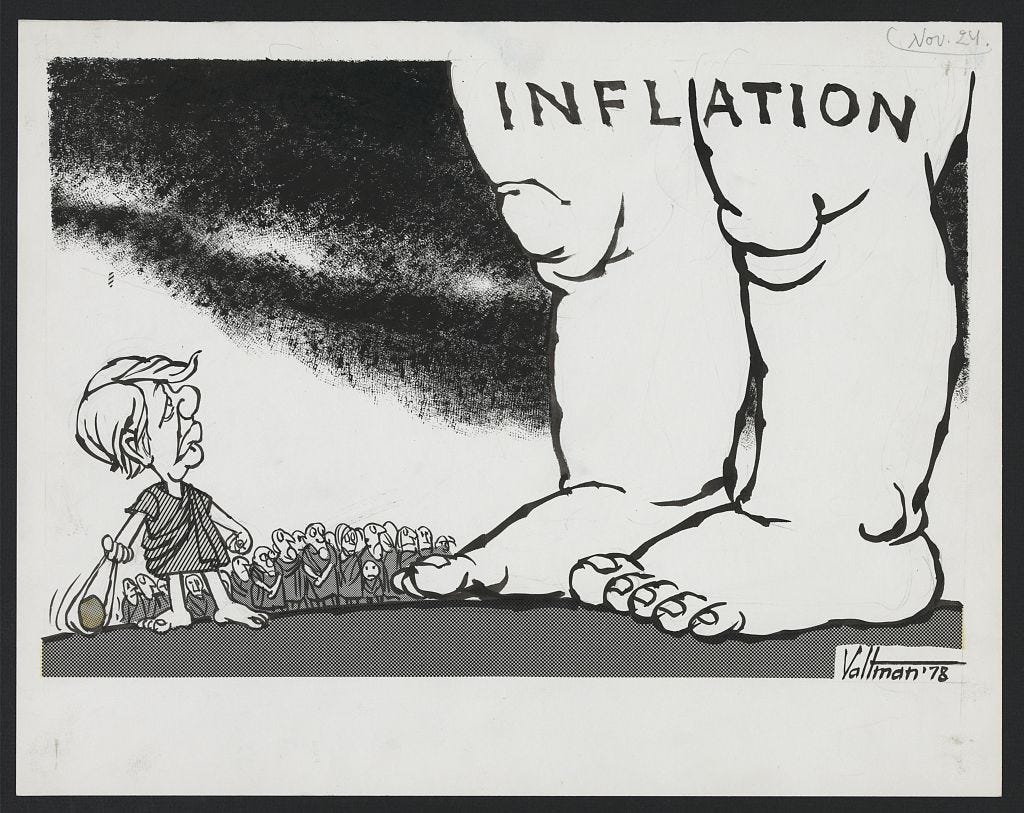

“A new era hardly renders the Great Inflation irrelevant. To the contrary, its history holds important lessons for the future. The simplest is this: Inflation, if it reemerges, ought to be nipped in the bud; the longer we wait, the harder it gets to rein in.”1

—ROBERT J. SAMUELSON, author of the Great Inflation and Its Aftermath

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

On August 23, 2024, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell used his speech at Jackson Hole to announce the FOMC’s intended pivot toward looser monetary policy.2 In my previous newsletter published on August 27, 2024, I argued that this was a mistake. Then, on September 18, 2024, the FOMC upped the ante by cutting the federal funds rate by 50 basis points, signaling a base case plan to enact a series of additional cuts by the end of the year, and then forecasting several more cuts in 2025. Financial history strongly suggested that this was a BIG mistake.

Surprisingly, most economists, investors, and financial journalists applauded what they believed to be the Fed’s commendable foresight rather than lamented what is more likely to be their tragic amnesia. I truly hope the future vindicates the Fed, but financial history strongly suggests that it won’t—and that was before the recent releases of the employment and CPI reports for September 2024, both of which exceeded expectations. The addition of 254,000 jobs and a 3.3% annualized increase in core inflation suggest that inflationary pressures are, at best, sticky and, at worst, already reigniting.

In short, faith that the Fed’s pivot will produce a victory over post-COVID-19 inflation now feels like the desperate hope one feels when a quarterback lobs a wobbly Hail Mary pass into a crowded end zone with no time on the clock. It’s possible that they are on the verge of victory, but it certainly doesn’t appear likely. It is, therefore, hard to consider the Fed’s play call as anything other than a grave, unforced error that is likely to have very real consequences.

The Fed’s Costly Habit of Overcompensating for Recent Mistakes

The Fed has made many mistakes over the past 110 years, but the worst ones tended to occur when they attempted to overcompensate for their most recent error rather than avoid a far more costly one. In the late 1920s, the Fed maintained loose monetary policy for far too long, in part, because they feared being blamed for the aggressive tightening in 1920 that triggered a deep recession in 1921. In the early 1930s, the Fed failed to backstop the banking system, in part, because they were blamed for overly accommodative monetary policies in the late 1920s. The subsequent implosion of the U.S. banking system unnecessarily deepened and prolonged the Great Depression.3

In 2024, the Federal Reserve seems utterly determined to loosen monetary policy early and prevent weakening of an otherwise strong labor market and economy. Once again, it appears the Fed is attempting to correct a recent mistake. In this case, the mistake was mislabeling inflation as “transitory” in 2021, and then belatedly tightening monetary policy to contain it.4 Loosening monetary policy early appears to be an overreaction to the Fed’s tardiness in 2021. The problem, however, is that financial history strongly suggests that loosening policy too early at the tail-end of a prolonged period of high inflation is far more likely to reignite inflation rather than extinguish it.

The Price of Unbalanced Monetary Policy

“‘Maximum’ or ‘full’ employment, after all, had become the nation’s major economic goal—not stability of the price level…Fear of immediate unemployment—rather than fear of current or eventual inflation—thus came to dominate economic policymaking.”5

—ARTHUR BURNS, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the Fed prematurely ended monetary policy tightening cycles on several occasions due, in large part, to a visceral fear of unemployment. Each time, it allowed inflation to reignite and burn even hotter. These failures caused the American people to lose faith in the Fed’s commitment to price stability, which allowed inflation expectations to become unanchored. As wages failed to keep pace with prices, strikes became more common and contentious. Unions negotiated progressively higher cost of living adjustments in labor contracts. Politicians called for (and even enacted) price controls after accusing companies of price gouging. Companies planned progressively higher price increases, and Americans altered their budgets to pay for them. Is this starting to sound familiar?

By the 1970s, higher inflation expectations were entrenched in the U.S. economy, making it increasingly difficult for the Fed to reestablish price stability with each passing year. The Great Inflation of 1965-1982 was a miserable period of U.S. history. Americans accepted that unaffordable mortgages, chronic shortages of gasoline, and paltry real returns from stocks were phenomena beyond their control. It was not until Fed Chairman Paul Volcker had the fortitude to initiate and sustain a draconian monetary policy from October 1979 to August 1982 that the Great Inflation finally concluded. But ending the vicious cycle was painful. The U.S. suffered a deep recession that lasted from July 1981 to November 1982, and unemployment that peaked at 10.8% in December 1982.6 Nevertheless, the benefits were worth the cost, as the end of the Great Inflation marked the beginning of a new era of economic prosperity.

The Financial Media is Channeling the Wrong Message

The airwaves are currently packed with pundits who talk endlessly about the intricacies of technical rules, such as the Taylor Rule and Sahm Rule, while they all but ignore a far more important rule established after the Great Inflation.7 The rule is quite simple: It is not enough for the Fed to merely extinguish the visible flames of inflation; they must also extinguish the embers that threaten to reignite it. In the fall of 2024, this meant that coming close to hitting the Fed’s two percent inflation target was not enough to justify a pivot in policy. The Fed will likely need to overshoot the target—and each time they fail, they will need to overshoot it by a progressively wider margin on the next attempt.

Contrary to the wishful thinking that now dominates the financial news, the September employment and CPI reports are not preliminary evidence of an impending soft landing. Instead, they are compelling evidence that the inflationary embers remain aglow and are at serious risk of reigniting. By pivoting prematurely to accommodative monetary policy, the FOMC likely recorded its first failure in the battle to end post-COVID-19 inflation—and the American people will pay a price for it.

Extinguishing Inflation Requires the Heart of a Hawk

In February 2022, my mother-in-law drafted the picture below. It shows a dove releasing a hawk from a cage in which it was imprisoned for forty years. At the time, it appeared that the hawks were free, and the doves would, at least temporarily, take their place in the cage. The aggressive monetary policy tightening that followed seemed to confirm this thesis. Unfortunately, it now appears that the Fed hawks were really just doves in disguise. By abandoning monetary policy tightening prematurely, they revealed their true nature.

The Great Inflation was a dreadful seventeen-year stretch, and the prospect of repeating it should strike fear in the hearts of the Fed leadership. It is a fear that should be felt far more intensely than the fear of incremental weakening of a strong labor market. I hope the FOMC redevelops this fear because history clearly demonstrates that once inflation becomes entrenched, each passing day makes it more difficult and painful to eradicate.

The doves masquerading as hawks at the Federal Reserve need to return to their cages. Dovish timidity is a recipe for failure in a battle to end protracted periods of high inflation. Extinguishing post-COVID-19 inflation requires a hawk’s heart, and this job is far too important to be left unfinished.

Disclaimer: This is a personal newsletter. Any views or opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not represent those of any people or organizations that the writer may or may not be associated with in a professional capacity, unless specifically stated. This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product, service, or considered to be tax advice. There are no guarantees investment strategies will be successful. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal.

Robert J. Samuelson, "The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence (New York: Random House, 2010).

It is important to note that, similar to all major financial events, reactions to recent mistakes was not the only cause of these errors. For example, another important factor in the late 1920s was the desire to support Post-World War I reconstruction in Europe. Keeping rates low in the United States reduced outflows of gold from Europe, which would otherwise force tighter monetary conditions during a critical period of recovery.

Although this mistake was understandable, it was not excusable. The two-year period of high inflation following the end of World War I and the Great Influenza strongly suggested that post-COVID-19 inflation would follow a similar course. The passage of one hundred years makes it understandable that the Fed overlooked this event, but it does not excuse the oversight entirely.

Arthur F. Burns, “The Anguish of Central Banking,” The Per Jacobsson Foundation, September 30, 1979.

Mark J. Higgins, Investing in U.S. Financial History: Understanding the Past to Forecast the Future (Austin: Greenleaf Book Group, 2024).

The excessive focus on these rules does not mean they are useless metrics. It just means that they are not the most important factors to consider at the present moment.

It feels like artificially low rates is a habit that's hard to kick, even after a few years of abstinence