A Dark Comedy of Errors in Washington

Short-Sighted Monetary, Trade, and Fiscal Policies Collide in 2025

“For practical purposes, the financial memory should be assumed to last, at a maximum, no more than twenty years. This is normally the time it takes for the recollection of one disaster to be erased and for some variant on previous dementia to come forward to capture the financial mind.1

—JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH

Over the past year, I had the privilege of making many guest appearances on podcasts to discuss how to use the lessons of financial history to explain current economic events. Among my favorites was a podcast with Russell Napier, who is the keeper of the Library of Mistakes in Edinburgh, UK. The Library offers several educational programs and maintains a vast collection of financial and economic history books. Its core mission is to continuously refresh the public’s collective memory of lessons learned from past financial traumas, and thereby reduce the probability of repeating them. Tragically, instinct still compels many people to ignore these lessons and, instead, learn by suffering the painful consequences of repeating them. Several financial mistakes affecting the world today fit squarely in this category.

This newsletter focuses on three big mistakes in the United States. All three were preventable if policymakers had heeded the lessons of history. Interestingly, unlike most financial mistakes, these three originated in Washington, DC rather than Wall Street. The first mistake was the Federal Reserve’s premature pivot to more accommodative monetary policy in September 2024. The second was the Trump Administration’s needless initiation of a global trade war on April 2, 2025. The third is the continued failure of the U.S. Congress to deal with chronic, unsustainable spending—especially on entitlement programs. In combination, these mistakes have caused unnecessary price instability, dangerous turmoil in financial markets, costly damage to international relations, and intensifying political polarization within the nation’s borders.

The good news is that the United States is no stranger to dark comedies, and it has an impressive track record of moving past them. The bad news is that the path is always painful and messy. Many people suffer during such periods, and the dark comedy of the 2020s is unlikely to be an exception.

Mistake #1: Failure to Learn from the Great Inflation

“American policymakers tend to see merit in a gradualist approach because it promises a return of general price stability—perhaps with a delay of five or more years but without requiring significant sacrifice on the part of workers or their employers. But the very caution that leads politically to a policy of gradualism may lead also to premature suspension or abandonment in actual practice.”2

—ARTHUR BURNS, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board

In August 2021, I published a paper on SSRN, entitled “Investors Can Temper Their Inflation Fears: Post-COVID Inflation is Unlikely to Resemble the Great Inflation of 1968 to 1982.” I argued that Post-COVID-19 inflation was unlikely to rise as high or last as long as it did during the Great Inflation of 1965 to 1982.3 Instead, I argued that it was more likely to resemble the Post World War I/Great Influenza inflation of 1919-1920, which lasted approximately two years. My thesis was contingent upon the belief that the Federal Reserve Board would avoid repeating the monetary policy errors that their predecessors made in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Unfortunately, the Fed’s actions over the past nine months revealed that this assumption was wrong. Despite a relatively strong economy and resilient labor market, on September 18, 2024, the FOMC pivoted to a more accommodative monetary policy by announcing a 50-basis point cut to the federal funds rate. Then, the FOMC followed with two additional 25 basis point cuts in November and December, respectively. With unemployment hovering around 4%, the Fed had clearly prioritized the employment side of their mandate at the expense of price stability. Concerned that the Fed was moving too soon and too fast, I published several newsletters warning that their actions would likely cause inflation to reignite.4

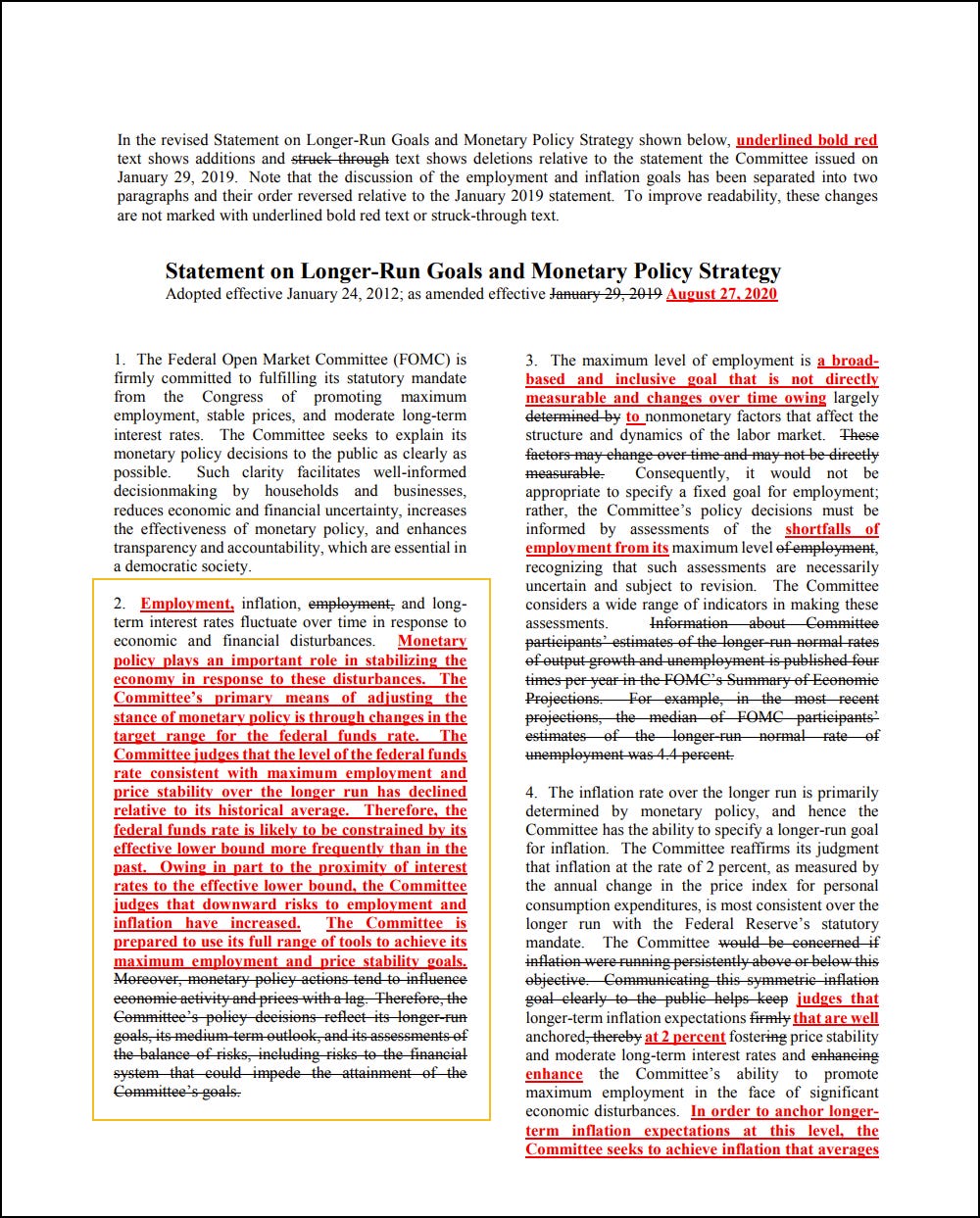

What was most disappointing about the Fed’s shift in policy was that the decision was not merely a function of unconscious bias. Discussions at a recent meeting of the Fed’s Shadow Open Market Committee (SOMC) revealed that the FOMC had intentionally prioritized the employment mandate. Former President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and member of the SOMC, Jeffrey Lacker, revealed this in an April 8, 2025 interview with Kathleen Hays on Central Bank Central. Specifically, Lacker recounted how the Federal Reserve symbolically expressed a bias toward full employment by intentionally moving the paragraph describing the Fed’s employment mandate ahead of the paragraph describing the inflation mandate in the 2020 revision of its policy framework statement (see the excerpt below). This almost certainly reinforced the Fed’s bias toward prioritizing full employment over price stability for the past five years. It also makes it less surprising—but no less disappointing—that the FOMC pivoted toward more accommodative monetary policy in September 2024 despite the fact that the labor market remained strong and inflation remained well above the 2% target.

Federal Reserve’s 2020 Revision to its Statement on Longer-Run and Monetary Policy Strategy

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (August 27, 2020).

Inflationary Pressures Reappear in 2025

In early 2025, the fear that inflation could reignite—or at least remain sticky—was validated. Trailing 12-month CPI metrics for January and February 2025 were stronger than anticipated and remained well above the Fed’s target of 2%. Meanwhile, labor markets remained tight, with unemployment still hovering around 4%.

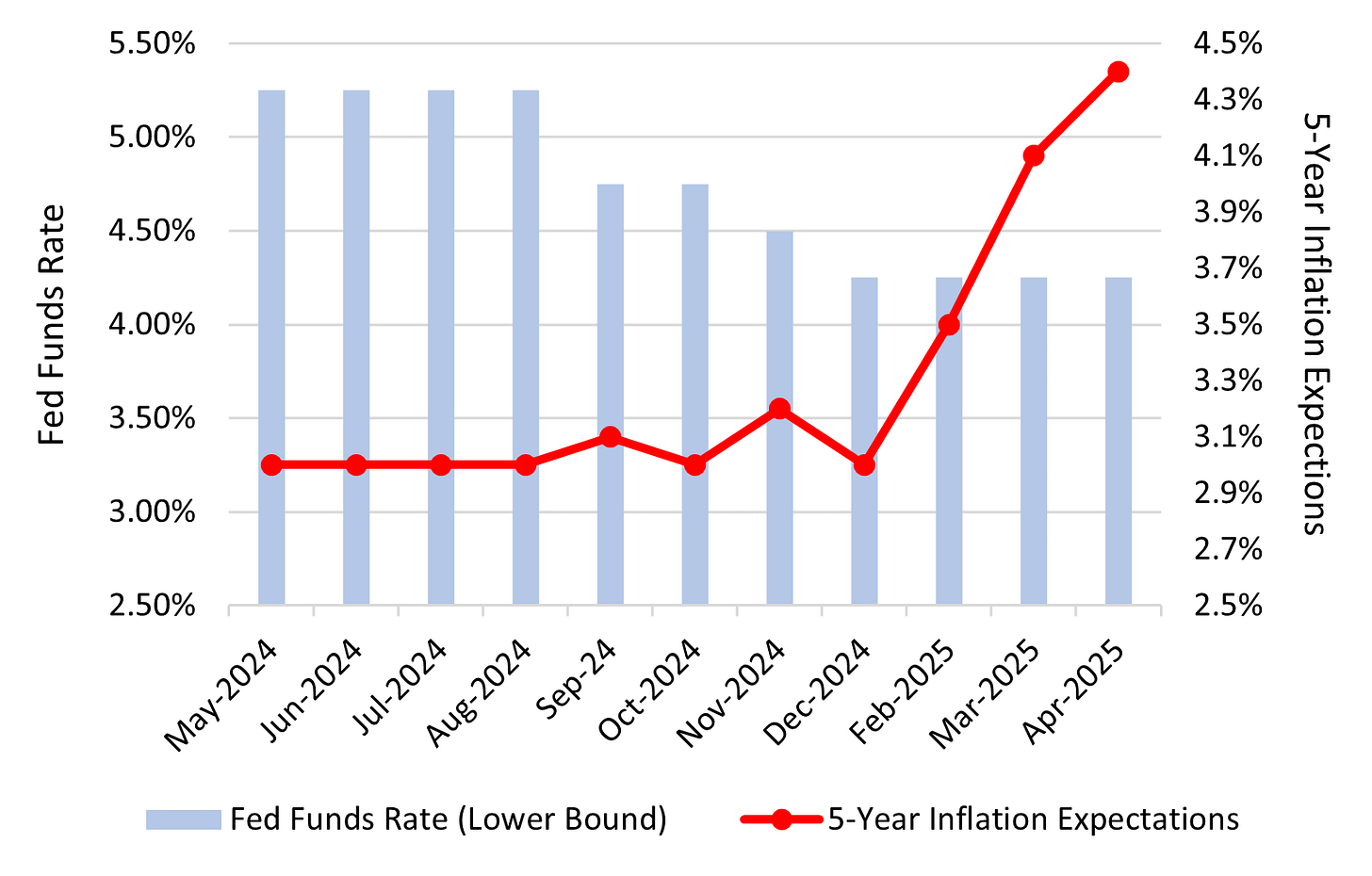

As if the CPI reports were not worrisome enough, the newly elected President Donald J. Trump soon fanned the inflationary flames by announcing aggressive tariff policies. This began almost immediately after the inauguration when President Trump announced plans to enact tariffs on Canada and Mexico. Over the next two and half months, President Trump expanded the list of affected countries and substantially increased tariff rates. The rapid escalation culminated in an announcement of sweeping tariffs affecting the entire world on April 2, 2025. The shocking announcement prompted major disruptions in global securities markets, while the expectation of higher prices caused consumer confidence to plummet and inflation expectations to rise. Figure 1 shows the rise of inflation expectations according to a survey administered by the University of Michigan (right axis), as well as the federal funds rate over the past 12 months (left axis) . While it is too early to predict how Trump’s policies will evolve and impact price stability over the next several months, the sharp increase in inflation expectations over the past two months is a bad omen.5

Figure 1: University of Michigan 5-Year Inflation Expectations (May 2024 - April 2025)

Source: University of Michigan

In summary, Trump’s tariff policies and the resultant trade war have compounded the Federal Reserve’s previous errors. That said, the effects of Trump’s tariffs on the global economy and international relations are far more concerning. These risks lie at the heart of the second mistake.

Mistake #2: Failure to Learn from the Great Depression

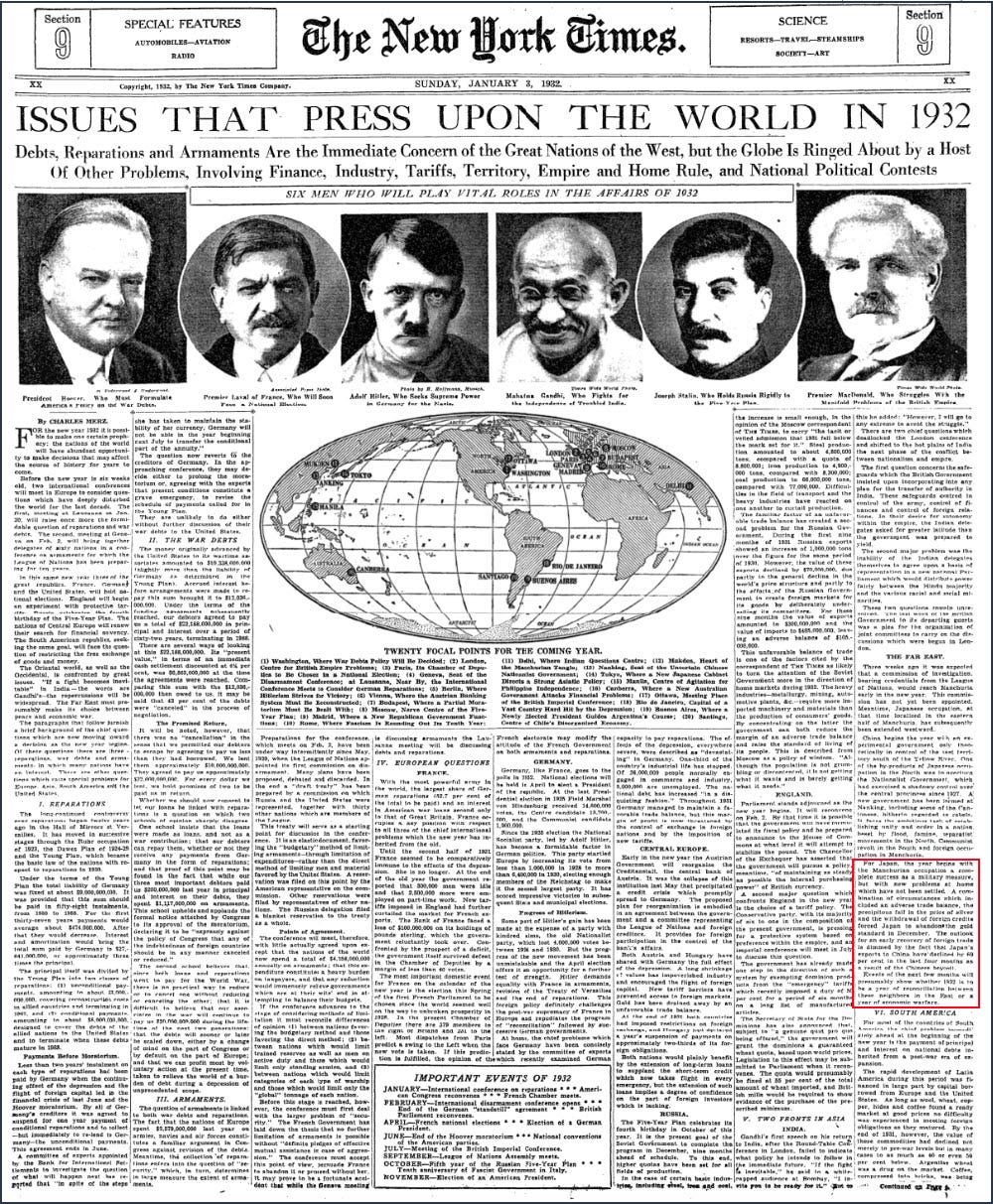

“For Japan, the year begins with the Manchurian occupation a complete success as a military measure, but with new problems at home...A combination of circumstances which included an adverse trade balance, the precipitous fall in the price of silver, and the withdrawal of foreign trade credits forced Japan to abandon the gold standard in December…Events of the next few months will presumably show whether 1932 is to be a year of reconciliation between these neighbors in the East or a year of economic warfare.”6

—THE NEW YORK TIMES (January 2, 1932)

Part 4 of Investing in U.S. Financial History is entitled “The Great Depression and Global Destabilization.” It begins with the deepening of the economic depression after the Great Crash of 1929 and ends with the surrender of Japan to Allied forces on September 2, 1945. The most important insight from Part 4 is that World War II likely would not have occurred if not for the Great Depression. Moreover, the Great Depression likely would not have occurred if not for short-sighted monetary, fiscal, and trade policies implemented by government policymakers throughout the world.

Source: The New York Times (January 2, 1932).

In the United States, the most significant error was the Federal Reserve’s failure to stop the spread of bank runs and subsequent collapse of the banking system in the early 1930s. A close second, however, was the ill-advised passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which President Herbert Hoover signed into law on June 17, 1930.7 The Act substantially raised tariffs on a variety of imports in an attempt to increase domestic production and reduce unemployment. History proved that the Smoot-Hawley Act failed to achieve these objectives. Instead, it triggered a series of retaliatory tariffs from trading partners and also inspired trading partners to erect new trade barriers with each other. These policies became known as “beggar-thy-neighbor” trade policies. Over the course of several years, they caused a dramatic reduction of global trade, thereby intensifying the effects of the Great Depression on all nations—including the United States.

The combined impact of the Great Depression and beggar-thy-neighbor trade policies were especially devastating in Germany and Japan. In the late 1920s, the Nazi party was relegated to the fringe of German politics, and it appeared it would soon fade into oblivion. But, Hitler effectively channeled the misery of the Great Depression and lingering bitterness over Germany’s treatment by the Allied Powers after World War I to revitalize the Nazi movement and establish himself as the dictator of the Third Reich. In Japan, the effects were even more pronounced. Starved of natural resources by the Depression and collapse of global trade, the Empire of Japan began a brutal campaign of colonization in Manchuria, China, and Southeast Asia. Fearful of Japan’s colonial expansion and brutal treatment of native populations, on August 1, 1941, the United States enacted an oil embargo, thereby depriving Japan of 80% of its oil imports. Left with a three-year supply of oil and having failed to negotiate a settlement with the United States, the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, thus drawing the United States into World War II.

The Danger of Trump’s Trade War

On April 2, 2025, the Trump Administration announced a sweeping array of tariffs affecting more than 180 countries. The tariffs were far higher than what nearly every economist anticipated, in part, because they were based on an inane formula allegedly concocted by the Trump Administration’s trade advisor, Peter Navarro. The formula was based only on the level of trade deficits rather than the presence of actual trade barriers. In effect, the actions by the Trump Administration constituted an opening salvo in an economic war on the world. Several nations responded with reciprocal tariffs, and the 1930s-like, tit-for-tat escalation intensified.

Investors predictably responded negatively to the escalating rhetoric. Global equity markets suffered double-digit declines within a matter of days. But, the far graver concern was a simultaneous sell-off of Treasury securities, which normally experience elevated demand when equity markets decline sharply. Faced with a growing panic among equity investors and potential deterioration of confidence in U.S. Treasuries, the Trump Administration announced a 90-day pause on most tariffs on April 9, 2025.

As of April 15, it remains unclear how the trade war will proceed. Will the Trump Administration settle for modest tariffs, which are unlikely to trigger a full blown trade war? Or will they challenge the world to a trade war by erecting far higher trade barriers? If the answer is the former, there is ample time for the United States to turn away from the abyss. If the answer is the latter, the world may be forced to learn a lesson by experiencing pain and suffering that few alive today have witnessed.

The good news is that the potential consequences of a global trade war are well-known and well-documented. The bad news is that government policymakers are prone to choose a path of needless repetition rather than prudent avoidance. Only time will tell which path the Trump Administration will choose.

Mistake #3: Failure to Immortalize the Wisdom of Alexander Hamilton

“He [Alexander Hamilton] ardently wishes to see it incorporated, as a fundamental maxim, in the system of public credit of the United States, that the creation of debt should always be accompanied with the means of extinguishment. This he regards as the true secret for rendering public credit immortal.”8

—ALEXANDER HAMILTON (January 9, 1790)

In the Spring 2025 issue of the Museum of American Finance’s Financial History magazine, I am publishing an article entitled “Short-Term Gains and Long-Term Pain: The History of U.S. Entitlements.” It explains how entitlement programs have gradually evolved and massively expanded over the past 235 years. The most rapid period of expansion occurred during the decades immediately following World War II. This was largely because Americans enjoyed an anomalous period of extraordinary wealth, which emboldened them to demand more from the government with each passing year. Even to this day, few Americans understand that the relative abundance of the 1950s was never destined to last. For more detail on this misperception, I encourage you to read a previous post, entitled “The Phantom Menace: Inflated Expectations.”

The Abandoned Principles of Alexander Hamilton

In 1790, the United States was effectively bankrupt. Many states had defaulted on bonds issued to fund the Revolutionary War, and in extreme cases, some states even failed to fully compensate veterans for their service in the war. President George Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton to serve as the nation’s first secretary of the Treasury and restore the nation’s impaired credit. Hamilton proceeded to consolidate the war debt of the states under the federal government and selectively raise tariffs to ensure adequate coverage of interest and principal payments.9 He also articulated two fundamental principles regarding the use of public debt in his First Report on the Public Credit. The first was that it should be used primarily to address public dangers, especially foreign wars. The second—which is expressed in the above quote—was that the debt should be extinguished when the danger subsided. In combination, the application of Hamilton’s programs and principles repaired the nation’s credit in 1790 and established a solid foundation for future economic growth.

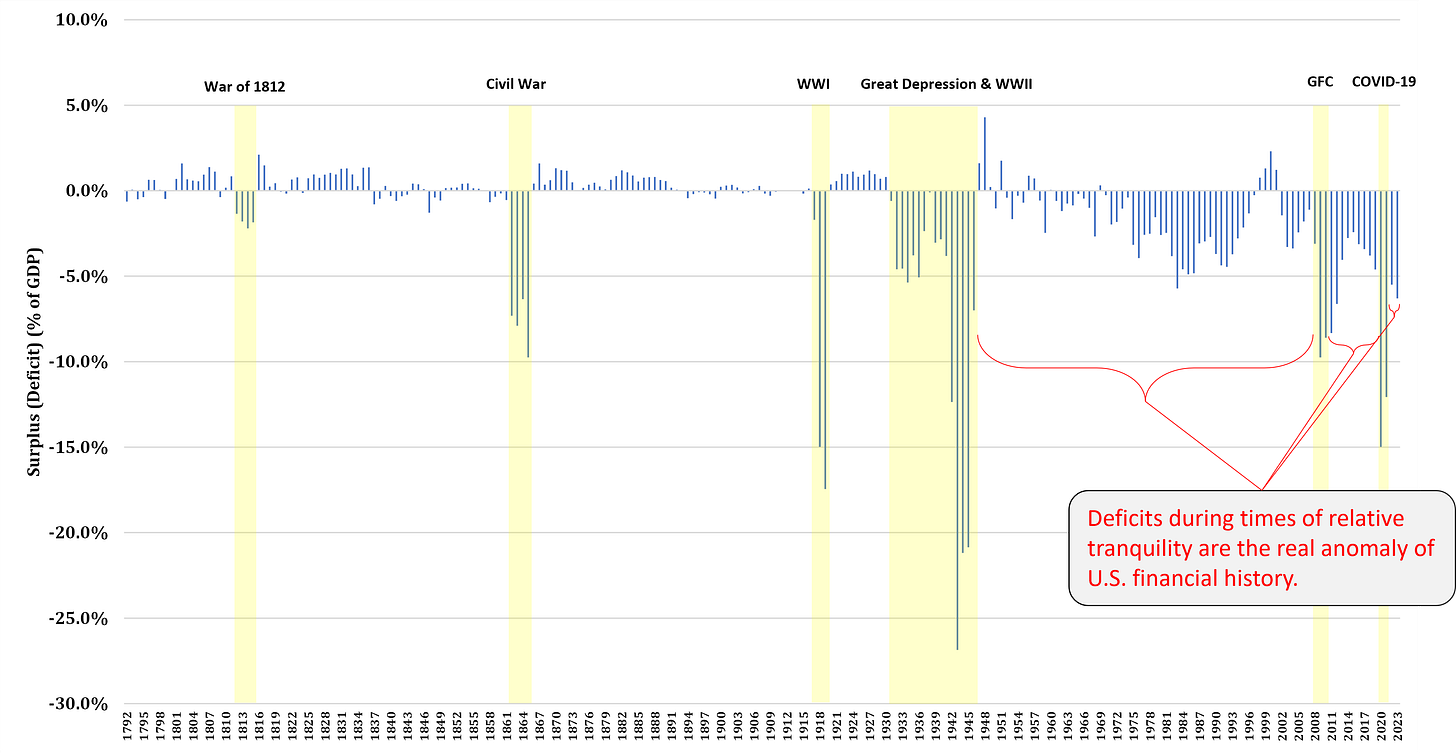

The United States largely abided by Hamiltonian principles for roughly 150 years, But by the end of the 1950s, these principles seemed all but forgotten. The federal government began running fiscal deficits regardless of whether public dangers existed, and it has continued running deficits in almost every year since (Figure 2). Now, mounting debt levels, combined with substantially larger deficits in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, have prompted a debt reckoning in the United States. Yet, even to this day, few politicians dare acknowledge that the primary driver of the nation’s fiscal imbalance is unsustainable spending on entitlement programs. The inconvenient truth, however, is that it is mathematically impossible for the United States to restore its fiscal health without making material changes to these programs. Doing so will require broad sacrifice from U.S. citizens. This will feel unfair to most, if not all, Americans called upon to sacrifice. Nevertheless, failure to act will prevent future generations from enjoying the same benefits and protections that current generations take for granted.

Figure 2: U.S. Federal Budget Deficits as Percent of GDP (1792-2023)

Source: Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789-1945 (Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1949).

Final Thoughts

The United States faces serious challenges in 2025. Persistent inflation, a damaging trade war, and chronic overspending are not easy problems to solve. Moreover, these challenges interact in ways that make each one even more difficult to surmount. For example, the Trump tariffs are designed to correct the perceived unfairness of the nation’s trade deficits. One of the major contributors to the nation’s trade deficits is the low rate of savings among Americans. At least in part, the incentive for Americans to save is weakened by the massive expansion of entitlement programs over the past 75 years.

Fortunately, there is good news as well. The truth is that Americans have confronted and overcome many challenges that seemed insurmountable in the past. This is because the United States is populated by enough people who possess the courage to confront intractable problems and creativity to design innovative solutions that stretch the limits of human imagination. The United States almost certainly faces many difficult years ahead, but history strongly suggests that the nation’s knack for solving the most vexing problems is also likely to repeat.

Purchase Investing in U.S. Financial History

Investing in U.S. Financial History is available in hardcover, audiobook, and eBook formats. Please note, however, that the eBook version was published in fixed format layout to ensure that graphics are more easily viewed. The eBook is ONLY intended to be read on large screens, such as tablets, laptops, or desktop computers.

Disclaimer: This is a personal newsletter. Any views or opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not represent those of any people or organizations that the writer may or may not be associated with in a professional capacity, unless specifically stated. This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product, service, or considered to be tax advice. There are no guarantees investment strategies will be successful. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal.

John Kenneth Galbraith. A Short History of Financial Euphoria. (New York: Viking Penguin, 1990).

I was still deep in the research phase of writing Investing in U.S. Financial History. I defined the Great Inflation as 1968-1982 in the paper. General consensus is that the Great Inflation lasted from 1965-1982. I have not updated the paper because keeping the time stamp is more important than making what I believe to be an immaterial edit.

Links to the three newsletters can be accessed here: Newsletter 1, Newsletter 2, and Newsletter 3.

In reality, tariffs are best thought of as a tax that can produce a one-time change in the price level. Nevertheless, the Trump tariffs almost certainly increased consumers’ inflation expectations. This is important because history has demonstrated that elevated levels of inflation expectations can produce a self-fulfilling prophecy on actual inflation, as most consumers fail to differentiate inflation caused by a temporary rise in price from a more permanent trend.

In the 1930s, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was more commonly referred to as “The Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act.” In this newsletter, it is referred to as “Smoot-Hawley” because it is now the more common convention.

Alexander Hamilton, First Report on the Public Credit (January 9, 1790). https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-06-02-0076-0002-0001